Really, I’m fine with you watering it down: Part I: 127 Hours and Conviction

If, according to screenwriter William Goldman (The Princess Bride, All the President’s Men), “In Hollywood, nobody knows anything,” then why is there always the need to taper off the intensity (read: effectiveness) of a movie in order to make it more palatable to a mainstream audience? Marketing is admittedly guesswork, and with the right evidence, you can prove that an R rated movie can make just as much as a PG-13. All three Matrix films are rated R, and feature no particularly offensive material, and yet they grossed over $1.6 billion worldwide. And those are fantasy films with no reality intruding whatsoever. In my talk with Going the Distance screenwriter Geoff LaTulippe, he admitted that his mean, nasty, and funny script was toned down, turning the main character played by Justin Long from a knowing asshole to a clumsy idiot. And boy did that concession work for the film in terms of being a financial juggernaut.

If, according to screenwriter William Goldman (The Princess Bride, All the President’s Men), “In Hollywood, nobody knows anything,” then why is there always the need to taper off the intensity (read: effectiveness) of a movie in order to make it more palatable to a mainstream audience? Marketing is admittedly guesswork, and with the right evidence, you can prove that an R rated movie can make just as much as a PG-13. All three Matrix films are rated R, and feature no particularly offensive material, and yet they grossed over $1.6 billion worldwide. And those are fantasy films with no reality intruding whatsoever. In my talk with Going the Distance screenwriter Geoff LaTulippe, he admitted that his mean, nasty, and funny script was toned down, turning the main character played by Justin Long from a knowing asshole to a clumsy idiot. And boy did that concession work for the film in terms of being a financial juggernaut.

It’s even stranger when a film’s subject matter already limits its appeal to a wide audience. This is true of Danny Boyle’s 127 Hours and Tony Goldwyn’s Conviction, both of which are based on a true story, but eliminate a lot of the details that differentiated them in the first place.

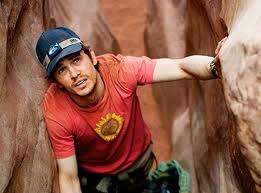

Boyle’s film is about Aron Ralston (played by James Franco), an X Games style mountain climber and overall outdoors extraordinaire, who gets stuck underneath a rock while recklessly scaling a mountain. Since he’s in the middle of Nowhere, Utah, his only way to survive is to slowly cut off his own arm, just as he’s running out of supplies. Now, considering the movie is based on Ralston’s book, you can probably guess whether or not he got out alive, but because it’s pretty faithful to the book (in an interview I was part of, Boyle said there were only two very minor changes in the film) as much, it lacks objectivity.

Boyle’s film is about Aron Ralston (played by James Franco), an X Games style mountain climber and overall outdoors extraordinaire, who gets stuck underneath a rock while recklessly scaling a mountain. Since he’s in the middle of Nowhere, Utah, his only way to survive is to slowly cut off his own arm, just as he’s running out of supplies. Now, considering the movie is based on Ralston’s book, you can probably guess whether or not he got out alive, but because it’s pretty faithful to the book (in an interview I was part of, Boyle said there were only two very minor changes in the film) as much, it lacks objectivity.

From what we see, Ralston’s kind of a simplistic guy, and since after an early excursion with a pair of attractive backpackers (Kate Mara and Amber Tamblyn*), he’s the only one we spend time with, and in one single set at that, this can get pretty tiresome. What do we learn about him in 90 minutes? He misses his ex-girlfriend and he wants to say goodbye to his parents, though he misses the point that his perpetual aloofness seems to have caused all the problems with his life, including his chutzpah in thinking he could scale this particular rock.

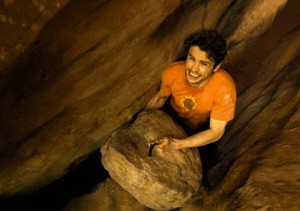

As a result, Boyle (Trainspotting, Slumdog Millionaire, 28 Days Later) has to fill up 127 Hours with his usual visual pyrotechnics that have worked so well for him in the past. There are triptychs showing us city life and music pumping up the excitement of being amongst all those people, its pro-industrialization message makes the film sort of an anti-Koyaanisqatsi. And really, I don’t blame Boyle for going this route; the scenes where he has to spruce up Ralston trapped by the boulder (it looks like he’s humping the rock while admiring himself in a mirror) don’t get interesting until he starts to hallucinate. Flashbacks and flash forwards are endless and tiresome (as is the closed shutter Gladiator-style photography), and Boyle’s dedication to the source material means he can’t give us any wrinkles that Ralston didn’t notice himself.

As a result, Boyle (Trainspotting, Slumdog Millionaire, 28 Days Later) has to fill up 127 Hours with his usual visual pyrotechnics that have worked so well for him in the past. There are triptychs showing us city life and music pumping up the excitement of being amongst all those people, its pro-industrialization message makes the film sort of an anti-Koyaanisqatsi. And really, I don’t blame Boyle for going this route; the scenes where he has to spruce up Ralston trapped by the boulder (it looks like he’s humping the rock while admiring himself in a mirror) don’t get interesting until he starts to hallucinate. Flashbacks and flash forwards are endless and tiresome (as is the closed shutter Gladiator-style photography), and Boyle’s dedication to the source material means he can’t give us any wrinkles that Ralston didn’t notice himself.

There’s no real subtext going on, except Boyle’s unintentional message that weaves its way through most of his movies (especially The Beach and Trainspotting) where it turns out that only conformity will save you, and individualism will get you punished. Granted the benchmarks for the lost in the mountains or trapped in a cave movies, Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole and Gus Van Sant’s Gerry, are rife with satire and sharp humor, something that Ralston doesn’t appear capable of. [There’s an unfortunate use of a song by Dido where the chorus is, “If I believe there’s more than this.” Nope.]

Since Boyle had to fill the frame with as many details as possible to pad out the film (the material might work better as a stage play, so we can have a real interior monologue), it’s a shame that he admittedly worried about audience squeamishness and felt the need to compromise based on how much he thought the audience could handle in terms of gore (and piss drinking, “it’s no Slurpee”), because there’s this constant feeling that the movie is about to get much more intense, and it simply never happens. Yes, the subject is inherently limited, and I wasn’t expecting the arrival of Nazis or Panamanian rebels for Aron to fight off (though Steven Seagal could have made a cameo and helped Aron out, he’s the go-to guy when you need one of your bones broken), but, and this is apparently directly from the novel, Aron is only in visible pain from the initial fall and arm crushing, never after, until he digs at his arm days later. Obviously, Ralston subconsciously wants us to believe that he’s a tough, resourceful guy, but that doesn’t mean we’d think he was a pussy because he expressed more than minor discomfort. Honesty is more interesting anyway.

Since Boyle had to fill the frame with as many details as possible to pad out the film (the material might work better as a stage play, so we can have a real interior monologue), it’s a shame that he admittedly worried about audience squeamishness and felt the need to compromise based on how much he thought the audience could handle in terms of gore (and piss drinking, “it’s no Slurpee”), because there’s this constant feeling that the movie is about to get much more intense, and it simply never happens. Yes, the subject is inherently limited, and I wasn’t expecting the arrival of Nazis or Panamanian rebels for Aron to fight off (though Steven Seagal could have made a cameo and helped Aron out, he’s the go-to guy when you need one of your bones broken), but, and this is apparently directly from the novel, Aron is only in visible pain from the initial fall and arm crushing, never after, until he digs at his arm days later. Obviously, Ralston subconsciously wants us to believe that he’s a tough, resourceful guy, but that doesn’t mean we’d think he was a pussy because he expressed more than minor discomfort. Honesty is more interesting anyway.

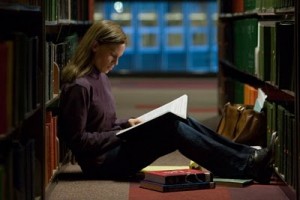

Tony Goldwyn’s Conviction suffers from an even greater lack of honesty and a need to make sure the audience is always comfortable with the material. Why that was deemed necessary when the story is about an uneducated New England woman, Betty Ann Waters (Hilary Swank) who goes to law school to become a lawyer just to free her white trashy brother, Kenny (Sam Rockwell), from prison because she believes he’s innocent, is obviously not going to appeal to small children. But that feeling that the director even knows what he’s doing completely dissipates after 20 minutes, once we get into the ill-conceived flashbacks about how protective Kenny was of Betty Ann when they were children and going from foster home to foster home.

Tony Goldwyn’s Conviction suffers from an even greater lack of honesty and a need to make sure the audience is always comfortable with the material. Why that was deemed necessary when the story is about an uneducated New England woman, Betty Ann Waters (Hilary Swank) who goes to law school to become a lawyer just to free her white trashy brother, Kenny (Sam Rockwell), from prison because she believes he’s innocent, is obviously not going to appeal to small children. But that feeling that the director even knows what he’s doing completely dissipates after 20 minutes, once we get into the ill-conceived flashbacks about how protective Kenny was of Betty Ann when they were children and going from foster home to foster home.

The flashback scenes introduce a theme that seems completely unintentional (and not just because the time-line is not often made clear causing a bunch of confusing details), and that’s that Kenny and Betty Ann have a strange incestuous thing going on. This is made more obvious because Betty Ann can’t even handle the notion that Kenny might be guilty of the murder, lashing out at and ex-communicating anyone who even suggests it, even though there’s no crucial bit of evidence that immediately comes up that would convince her that he’s innocent. It isn’t until years later when Betty Ann discovers that DNA could free him, since there wasn’t a court-admissible technology available when Kenny was convicted in 1983.

The flashback scenes introduce a theme that seems completely unintentional (and not just because the time-line is not often made clear causing a bunch of confusing details), and that’s that Kenny and Betty Ann have a strange incestuous thing going on. This is made more obvious because Betty Ann can’t even handle the notion that Kenny might be guilty of the murder, lashing out at and ex-communicating anyone who even suggests it, even though there’s no crucial bit of evidence that immediately comes up that would convince her that he’s innocent. It isn’t until years later when Betty Ann discovers that DNA could free him, since there wasn’t a court-admissible technology available when Kenny was convicted in 1983.

Now, just like 127 Hours, the ending should be clear to anyone even familiar with a courtroom drama (why would they make a movie about her if she couldn’t get him out?), but the simplification of the material is the frustrating part. The feminist cop is out to get Kenny because he was rude to her. The DA (Martha Coakely) won’t admit new evidence because she doesn’t want to re-open one of her defining cases. Kenny’s ex-lover (Juliette Lewis) frames him because she’s scared, but mostly she’s dirty, nasty trash. And on the other side of the female symmetrical pyramid Betty Ann is kind, wonderful and devoted to her brother and her kids. Her best friend played by Minnie Driver is endlessly patient and willing to take the brunt of Betty Ann’s frustration. The kindly old woman who works at the county clerk’s office is willing to dig through mountains and years of evidence, more than once, just to help Betty Ann.

In a way, since Conviction presents the female characters as front and center, it makes the film unique. But the movie seems to ignore that the real turning points are based on what the men do and the woman are mostly bystanders. Kenny committed the crime, but Rockwell doesn’t have much to do besides hick it up and be a jovial guy with a short fuse who loves his daughter. Betty Ann’s husband leaves her because she’s obsessed with the case, and her kids (who seem to be 13 years old for about 10 years) side with dad because she never pays attention to them. And Barry Scheck (a super-nebbish in real life, played, in a spectacular bit of miscasting, by Mr. Eyebrows, Peter Gallagher) is the one who really gets the case going because he was the one running “The Innocence Project” which freed wrongly convicted prisoners because of DNA evidence; he used his substantial media connections to shed light on Kenny’s case.

In a way, since Conviction presents the female characters as front and center, it makes the film unique. But the movie seems to ignore that the real turning points are based on what the men do and the woman are mostly bystanders. Kenny committed the crime, but Rockwell doesn’t have much to do besides hick it up and be a jovial guy with a short fuse who loves his daughter. Betty Ann’s husband leaves her because she’s obsessed with the case, and her kids (who seem to be 13 years old for about 10 years) side with dad because she never pays attention to them. And Barry Scheck (a super-nebbish in real life, played, in a spectacular bit of miscasting, by Mr. Eyebrows, Peter Gallagher) is the one who really gets the case going because he was the one running “The Innocence Project” which freed wrongly convicted prisoners because of DNA evidence; he used his substantial media connections to shed light on Kenny’s case.

But all that wouldn’t matter if the movie were effective dramatically, instead of being histrionic, melodramatic, heavy-handed, and with no self-awareness at all. My first reaction to Hilary Swank’s performance was that it was broad, ridiculous, and mired in clichéd New Englandisms, especially with the accent. But then I met the real Betty Ann Waters (who was doing a press tour with Rockwell and Goldwyn) and realized the accent is just right and Betty Ann probably was a broad, ridiculous mess. On the other hand, Rockwell’s performance seems pretty lazy, throwing in dramatically convenient rage. His scenes appear pre-programmed, he either has to be excited or suicidal. Fine, his actions are compressed because it takes place over a period of 18 years (though Rockwell looks nothing like the real Kenny at any time in his life), but it outlines the lack of gray area in every element of Conviction. Goldwyn even nixes the most painfully ironic fact, that Kenny died 6 months after he got out because he fell from a 15-foot wall while he was taking a shortcut to his brother’s house. In the interview, Goldwyn admitted this was because it was simply too much dramatically for the audience to handle (it’s even eliminated from the final bits of information typed out before the closing credits). I don’t know, I think I’d rather have cruel irony than no irony at all.

* Their scenes are not well written, he’s clearly flirting with them for hours and yet one of them says, as he’s leaving as to whether he’ll think about them later that “I don’t think we even figure into his day.”

Both of these films were screened as preparation for the Philadelphia Film Festival which runs Oct 14-24th.